Same Plan, But Different Words: Obama and Romney On The Israel-Iran Issue

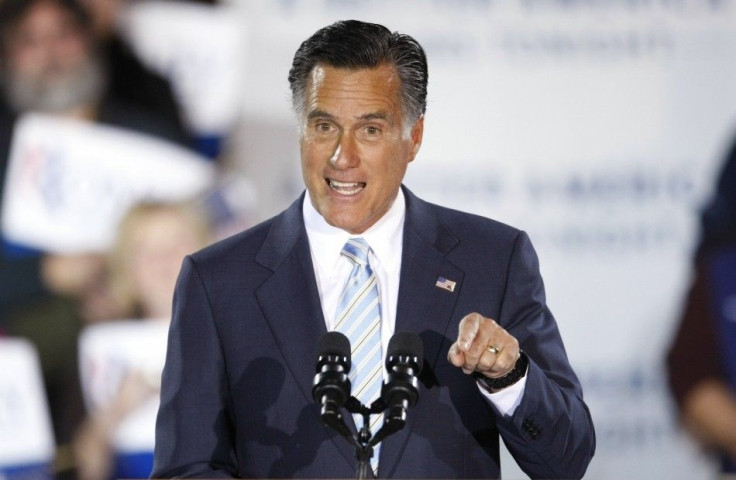

Hoping to distance himself from President Barack Obama, Mitt Romney took a hard stance on the stalemate between Israel and Iran during his visit to Jerusalem this weekend. Calling the prospect of Iran developing a nuclear weapon the "highest national-security priority," and saying, in no uncertain terms, that he would support a military strike if necessary, Romney sought to earn some foreign policy capital at home, as well as in Israel, one of the United States' most important allies.

As a presidential candidate, Romney is popular in Israel. A June poll from the Begin-Sadat Center for Strategic Studies found that a majority of Israelis believe that Romney "would better promote Israel's interests" than Obama would.

Although Romney's biggest hurdle before his trip was that "Israelis don't know anything about him," what the "Israeli public does know about Romney is that he is not Obama -- reason enough, in the minds of many, to like him," according to the Jerusalem Post. Since taking office four years ago, Obama has had a difficult relationship with Israel. In 2009, Obama made few friends by criticizing Israeli settlements in the Palestinian territories, and in a 2011 speech the president gaffed by endorsing a return to Israel's 1967 borders.

Notably, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu and Obama butted heads over the Iran issue this spring, when Netanyahu was ready to send his jets over the Persian Gulf.

Romney and Obama essentially have identical stances on Iran: On Sunday, Romney stated that the U.S. "should employ any and all measures to dissuade the Iranian regime from its nuclear course, and it is our fervent hope that diplomatic and economic measures will do so ... In the final analysis, of course, no option should be excluded. We recognize Israel's right to defend itself, and that it is right for America to stand with you." In March, Obama said that "both the Iranian and the Israeli governments recognize that when the United States says it is unacceptable for Iran to have a nuclear weapon, we mean what we say," adding, quite specifically, in a meeting with Netanyahu that "all options are on the table," including military intervention.

Still, Romney is seen as being tougher on Iran than the incumbent, which could not only increase his standing in Israel but also with voters in the United States, especially among the coveted evangelical vote.

On Friday, Obama sent $70 million in additional military aid to Jerusalem for its Iron Dome missile-defense system by signing the United States-Israel Enhanced Security Cooperation Act, while the Romney campaign, a day later, said that "standing by Israel does not mean with military and intelligence cooperation alone" and took jabs at Obama for the "distance" he's created between himself and Netanyahu.

Additionally, despite having largely the same plan for the Iranian issue, Romney has used particularly harsher rhetoric, accusing the Islamic Republic of having a "bloody and brutal record" and "malevolent intentions," and adding that "we must not delude ourselves into thinking that containment is an option."

Romney also seems more willing, at least in his speeches, to use the military option, whereas Obama says, when challenged to do so, that it's a last resort. Where Obama says that a "nuclear-free Iran" is "required for international security," Romney says there is "no reason to trust [Tehran] with nuclear material." The language is harsher, but the meaning is the same.

In the meantime, Obama is able to follow through on his plans while the Republican nominee can only comment from the sidelines. On Sunday, Defense Secretary Leon Panetta said the White House, by tightening sanctions against Iran, is sending "a very strong message to them that they can't continue doing what they're doing."

© Copyright IBTimes 2025. All rights reserved.